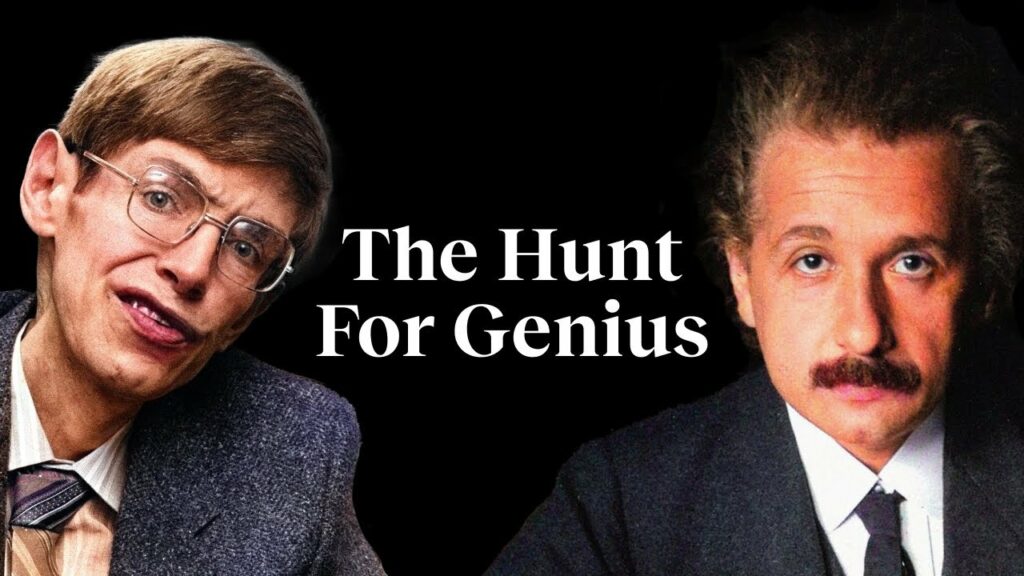

Genius sells. Publishers of biographies and studios behind Oscar-winning dramas can tell you that. So can network scientist Albert-László Barabási, who has actually conducted research into the nature of genius. “What really determines the ‘genius’ label?” he asks in the Big Think video above. When he and his collaborators “compared all geniuses to their scientific peers, we realized that there are really two very different classes: ordinary genius and peerless genius.” Considering the latter, Barabási points to the perhaps unsurprising example of Albert Einstein.

“When we looked at the scientists working at the same time, roughly in the same areas of physics that he did,” Barabási explains, “there was no one who would have a comparable productivity or scientific impact to him. He was truly alone.” Illustrating the class of “ordinary genius” is a figure almost as well-known as Einstein: Stephen Hawking. “To our surprise, we realized, there were about six other scientists who worked in roughly the same area, and had comparable, often bigger impacts than Stephen Hawking had” — and yet only he was publicly labeled a “genius.”

“The ‘genius’ label is a construct that society assigns to exceptional accomplishment, but exceptional accomplishment is not sufficient to get the genius label.” Throughout history, “remarkable individuals were always born in the vicinity of big cultural centers, and everything that is outside of the cultural centers was typically a desert of exceptional accomplishments.” Today, as venture capitalist and essayist Paul Graham once wrote, “a thousand Leonardos and a thousand Michelangelos walk among us. If DNA ruled, we should be greeted daily by artistic marvels. We aren’t, and the reason is that to make Leonardo you need more than his innate ability. You also need Florence in 1450.”

What would it take to discover the “hidden geniuses” who may have been born into unpropitious circumstances? This is one concern behind Barabási’s inquiry into the nature of scientific prominence. The question of “how does the quality of the idea that I picked, and the ultimate success, and my ability as a scientist connect to each other” led him to develop the “Q factor,” the measure of “our ability to turn ideas into discoveries.” His analysis of the data shows that, throughout a scientist’s career, the Q factor remains more or less stable. Applying it to big data “could help us to discover those that really had the accomplishment and deserve the genius label and put them in the right place.” If he’s correct, we can expect a bumper crop of books and movies on a whole new wave of geniuses in the years to come.

Related content:

What Character Traits Do Geniuses Share in Common?: From Isaac Newton to Richard Feynman

This is What Richard Feynman’s PhD Thesis Looks Like: A Video Introduction

Neil deGrasse Tyson on the Staggering Genius of Isaac Newton

Explore the Largest Online Archive Exploring the Genius of Leonard da Vinci

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.