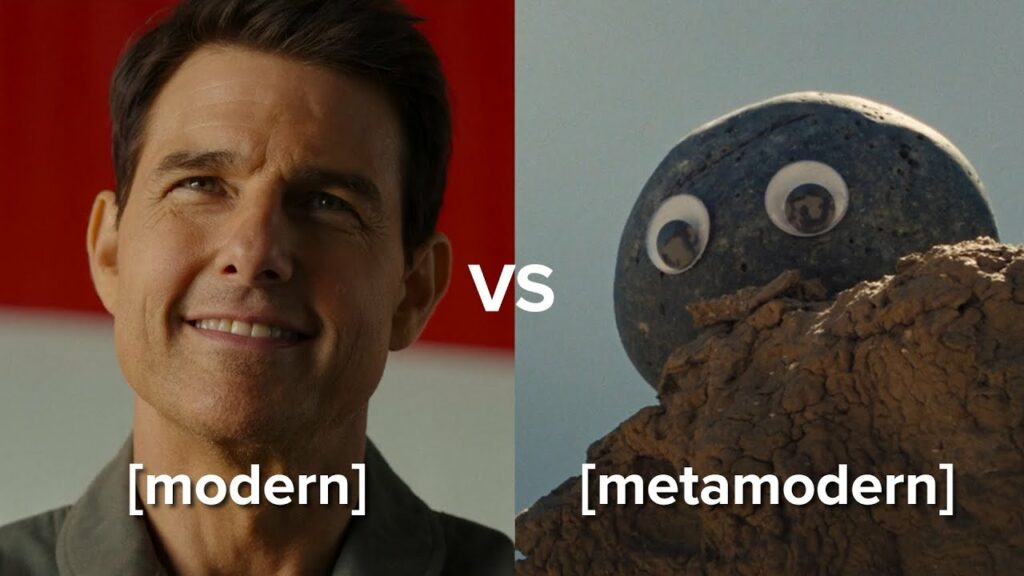

Say what you will about Joker; it did, at least, feel like a real movie, which is hardly true of many, if not most, of the influential feature films that have come out since. Yes, they run between 80 and 180 minutes, and yes, they were screened in theaters (though increasingly many viewers have opted to stream them at home), but despite their often considerable entertainment value, they somehow never quite satisfy. If they feel weightless to us, even trivial — shot through with not just irony and self-reference, but also jarring lapses into emotional kitsch — that must owe in large part to the impression that their creators don’t quite take their own art form seriously. Filmmakers surely still want to believe in film, but can’t be seen believing in it too strongly: this is the dilemma of our meta-modern age.

“Just in the year 2022, we saw Nope, which criticizes spectacle even as it tries to be one; The Banshees of Insherin, which is in dialogue with itself about the value of art; we saw Steven Spielberg looking back at his own life in The Fabelmans, and examining the role cinema has played in it for both good and bad — through cinema.” Thomas Flight names these pictures as examples in his new video essay on meta-modernity, a term of recent enough coinage to require definition from a variety of angles. “It seems like there’s very little straightforward storytelling in film anymore,” he says. “Movies are either part of a multidimensional franchise or are satirical, surreal, or absurd. They might contain a multiverse or twists on a classic trope, break storytelling convention, or some combination of all these things.”

No single production pulls as many of these tricks as last year’s Academy Awards-dominating Everything Everywhere All at Once (the subject of a previous Thomas Flight video essay). As much a zeitgeist picture of the early twenty-twenties as Joker was of the late twenty-tens, it shows us where cinema has arrived — for better or for worse — after its nearly century-and-a-half long journey through modernism, post-modernism, and now meta-modernism. Modernism, as Flight defines it, promotes “an objective view of reality” and “displays specific values, and then unapologetically seems to argue for those values as good and beneficial.” When those values were eventually called into question, post-modernism arose “to question the value of narrative itself.” Here Flight quotes films like Apocalypse Now, F For Fake, Blade Runner, Blue Velvet, Barton Fink, Pulp Fiction, suggesting that post-modernism was very good indeed for cinema, at least at first.

But “irony, pastiche, surrealism, and self-reflexivity” inevitably hit the saturation point; “you can only subvert expectations so many times before the new expectation becomes that expectations will be subverted, and it all starts to get a little bit old.” As post-modernism responded to modernism, so meta-modernism responds to post-modernism, attempting to lay claim to the power of both cultural periods at once. We see this in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, as well as most of the oeuvre of Wes Anderson — but also in a lot of “swinging wildly back and forth between modernist sincerity and postmodern deconstruction,” little of it more convincing than the latest CGI extravaganza extruded by any given superhero franchise. Still, it’s early day in our era of meta-modernity; when its arts reach maturity, perhaps we’ll wonder how we ever saw the world before them.

Related Content:

David Foster Wallace on What’s Wrong with Postmodernism: A Video Essay

Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood Examined on Pretty Much Pop #12

How Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner Illuminates the Central Problem of Modernity

Nietzsche and the Postmodern Condition: A Free Philosophy Course by Rick Roderick

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.