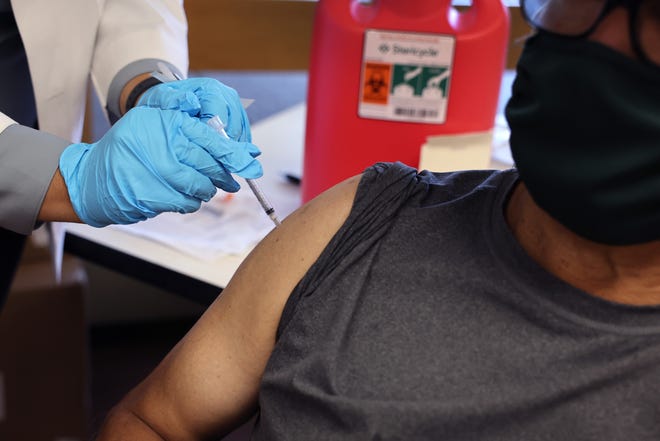

When COVID-19 vaccines entered the commercial market last fall, the federal government introduced a program to make shots accessible to people with limited coverage or no insurance. That program – which provided millions of free shots to low-income people – is now coming to a halt, U.S. health officials said.

The Bridge Access Program is set to end in August, months earlier than local health departments and health centers expected because when pandemic-era funding from Congress is expiring. Biden administration officials are seeking permanent funding so that routine vaccinations can remain free for adults, through a program akin to the long-standing Vaccines for Children program, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention official said via email.

Health access:Imagine if the government offered dental care. New federal rule could make that a reality.

Leaders at health centers and departments said without the Bridge Access Program, they’re worried about how they’ll secure funding for vaccines in preparation for the winter respiratory viral season when hospitalizations and deaths tend to increase. Many low-income Americans may be unable to afford vaccines for the novel coronavirus and its myriad variants. Updated vaccines will be formulated to target these strains, but pandemic-era funding will be gone.

“Money is not limitless, but COVID is still with us,” said Frederica Williams, CEO of the Whittier Street Health Center, a Federally Qualified Health Center that predominantly serves lower-income communities of color in Boston. The program has tapped into Bridge Access funds to administer vaccines.

About a fifth of the center’s patients are uninsured, including many new migrants from Haiti and Central and South America, Williams said. This doesn’t include others – like ride-share drivers or restaurant staff – who may have some health insurance but don’t get insurance coverage for vaccines.

Last fall CDC Director Dr. Mandy Cohen visited the Whittier Street Health Center to promote the updated COVID-19 vaccine. The sudden halt in funding was startling to Williams. As of this week, she said, the health center hasn’t received notice about the Bridge Access Program ending.

Leaders at the National Association for Community Health Centers, a nonprofit advocacy group, said they knew the program was temporary, but were surprised to hear it was ending this August. As looming respiratory illnesses such as flu, RSV and COVID-19 increase in the colder months this year, health centers will continue to immunize people daily, said Sarah Price, the association’s director of public health integration, in a statement. “Health centers will either stock these vaccines or refer to resources within their community – with an aim to addressing access barriers and closing the loop,” she said.

Since Bridge Access launched on Sept. 13, 2023, it has provided more than 1.4 million free COVID-19 vaccines through retail pharmacies, community health centers and public health departments across the U.S., David Daigle, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention spokesperson, said in an email. The CDC did not respond to inquiries about whether the agency told health centers and departments the Bridge program would be ending in August.

“After August, there may be a small amount of free vaccine available through health department immunization programs, but supply would be very limited,” Daigle said, in an email first shared on social media by a CBS News reporter. “We don’t yet know if the manufacturers will have patient assistance programs.”

Vaccine manufacturers Novavax and Pfizer said via email they planned to assess their accessibility options for U.S. consumers in the wake of this change and help ensure the vaccines were accessible for uninsured and underinsured patients. Moderna did not respond to a request for comment.

When a federal panel broadly recommended the updated vaccine in September, many people ran into barriers trying to pay for vaccines. Major U.S. pharmacies were charging upward of $100 a dose. At that time, the Bridge Access Program became a beacon, cited by many on social media, offering shots for people having trouble affording them.

The loss of the program has made health officials worry about an uptick in cases.

“This is creating a barrier that could lead to much larger resurgences of COVID,” said Dr. Walter Orenstein, associate director at the Emory University Vaccine Center. Orenstein formerly worked as the U.S. National Immunization Program director with the Vaccines for Children program launch in the 1990s and foresees trouble if vaccines are not made more accessible.

“I hope I’m wrong. But I think that (it’s) better to remove barriers to access when we have such safe and effective vaccines than to prevent people from wanting those vaccines to get vaccinated.”

Mental health:What can prevent suicide? A place to call home, a person to reach out to

The U.S. has reached a record low of uninsured people, the Department of Health and Human Services announced in August. However, about 7.7% of the population, or around 25 million people, still don’t have health insurance. Among adults 18 and older, 11% are uninsured. Experts say many without insurance are people of color and immigrants. Uninsured people also tend to be younger, lower income and live in Southern states that have not expanded Medicaid access. This demographic group includes millions of undocumented people who don’t qualify for federal health coverage.

In addition, millions of adults have less-than-robust health coverage through their employer and many earn too much to qualify for Medicaid. People in this category likely would have had difficulty getting a COVID-19 vaccine without Bridge Access funding.

The vaccine funding is ending as Medicaid is being rolled back across the U.S. Nearly 22 million people who had Medicaid during the pandemic have been disenrolled as of May 10, according to KFF, a nonpartisan health policy organization.

North Carolina is an exception, where the state legislature expanded Medicaid to adults in late 2023. The state has seen a smaller drop in Medicaid enrollment than elsewhere in the country. The state covered the cost of preventative vaccines, according to Raynard Washington, the director of the Public Health Department for Mecklenburg County, which includes Charlotte.

About 13% of the county’s adult population is uninsured, Washington said. These patients are disproportionately Latino and foreign-born. Many of the county’s underinsured, who also received the vaccines, are working in jobs without benefits or earned too much to get Medicaid.

Washington, who chairs the Big Cities Health Coalition, a consortium of top U.S. health officials, thinks Congress should work toward improving public health systems rather than chip away at initiatives that have been put in place since the pandemic. He said it’s important to invest in vaccines to protect yourself and

He said it’s important to invest in vaccines to protect yourself and others at risk of severe illness.

“In the case of COVID, of course, we know there are people who are still very vulnerable to severe illness,” Washington said. ” “So these vaccines are in many ways, lifesaving for some folks.”

Washington’s coalition supports the Biden administration’s Vaccine for Adults proposal, which has fallen short of passing.

It’s not time to step away from preventing COVID-19, he said.

“We’ve got to invest in both times of crisis, and when we’re not in crisis,” he said.

The next round of COVID-19 vaccines – intended to target dominating strains – has not been released. When it is, Washington expects local and state jurisdictions would cover the cost with other resources.

At the Whittier Street center in Boston, Williams said she recently got a call from two patients who tested positive for COVID-19.

The Haitian man and woman Williams had met through a local church program and asked about antiviral medication available through the state’s public health department. They were uninsured. She told them the program they were asking about ended in March, but the Whittier center would cover their treatment regardless of insurance.

The need for care remains, even if the pandemic has eased up, she said.

“We just have to figure out a way, as we’ve always done, to make sure that we continue to remain true to our mission,” she said.

Getting You Seen Online

Thank You! Source link