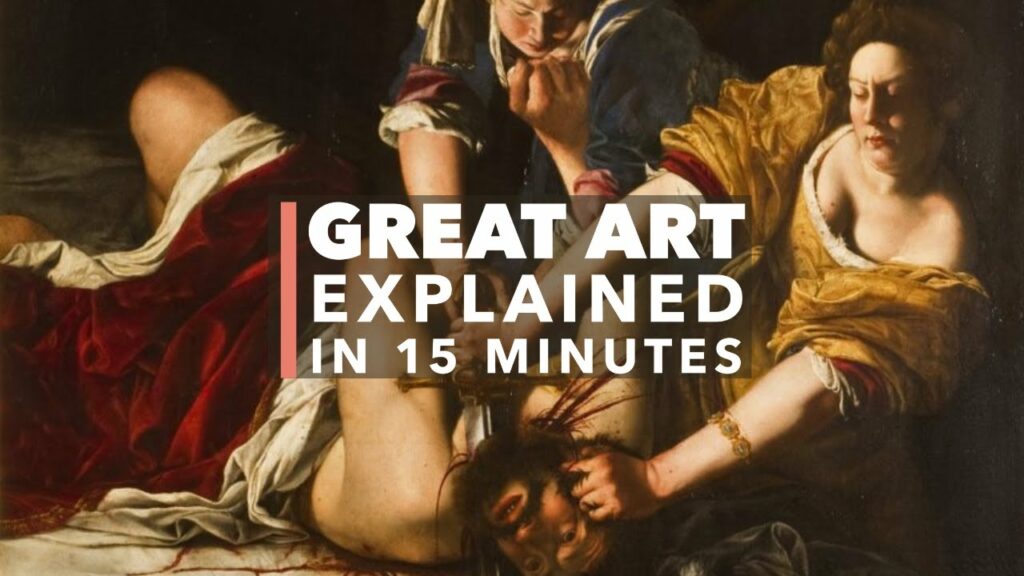

Today, the name Judith hardly calls to mind a woman capable of great violence. Things seem to have been different in antiquity: “The Biblical story from the Book of Judith tells how the beautiful Israelite widow Judith bravely seduces and then kills the sexually aggressive Assyrian general Holofernes in order to save her people,” says gallerist-Youtuber James Payne in the Great Art Explained video above. “It was seen as a symbol of triumph over tyranny, a sort of female David and Goliath.” It thus made the ideal subject matter for the painter Artemisia Gentileschi, who followed in the footsteps of her father Orazio Gentileschi, and who gained notoriety at a young age for her involvement in a major sex-crime trial.

As Rebecca Mead writes in the New Yorker, “Artemisia was raped by a friend of Orazio’s: the artist Agostino Tassi,” who had been hired to tutor her. Though Tassi promised to marry her after that and subsequent encounters, he never made good — and indeed married another woman — which prompted Orazio Gentileschi to seek recompense for the family’s lost honor in court. In our time, “the assault has inevitably, and often reductively, been the lens through which her artistic accomplishments have been viewed. The sometimes savage themes of her paintings have been interpreted as expressions of wrathful catharsis.” This is truer of none of her works than Judith Beheading Holofernes, the subject of Payne’s video.

“Even for seventeenth-century Florence, this painting was unusually gruesome,” he says, “and even more unusual was that it was painted by a woman.” What’s more, it came a couple of decades after a rendition of the same Biblical event by no less a master than Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. “Caravaggio dominated the art scene in the seventeenth century, and he was also a good friend of Gentileschi’s father,” which means that Artemisia could have received his influence directly. Both of their images of Holofernes’ death at Judith’s hands are “pure Baroque paintings: exaggerated movement, high contrast light set off by deep dark shadows, contorted features and violent gestures, a focus on the theatrical.”

Yet with its intense physicality — as well as its frankness about Judith and her maidservant’s concentration on their murderous task — Artemisia’s painting makes a greater impact on viewers. Mead notes that it “was for decades hidden from public view, presumably on the ground that it was distasteful” and that it moved nineteenth-century art historian Anna Brownell Jameson to wish for “the privilege of burning it to ashes.” Though the artist fell into obscurity after her death, the culture of the twenty-first century has elevated her out of it: “on art-adjacent blogs, Artemisia’s strength and occasionally obnoxious self-assurance are held forth as her most essential qualities. She has become, as the Internet term of approval has it, a badass bitch.” Nor has her name hurt her brand. Artemisia: now there’s a formidable-sounding woman.

Related content:

A Short Introduction to Caravaggio, the Master Of Light

What Makes Caravaggio’s The Taking of Christ a Timeless, Great Painting?

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.