“In the criminal justice system,” the evergreen Law & Order‘s opening credits remind us, “the people are represented by two separate, yet equally important, groups: the police, who investigate crime; and the district attorneys, who prosecute the offenders.”

They fail to mention the life-sized skeleton with ghastly glowing eyes and a camera tucked away inside its skull.

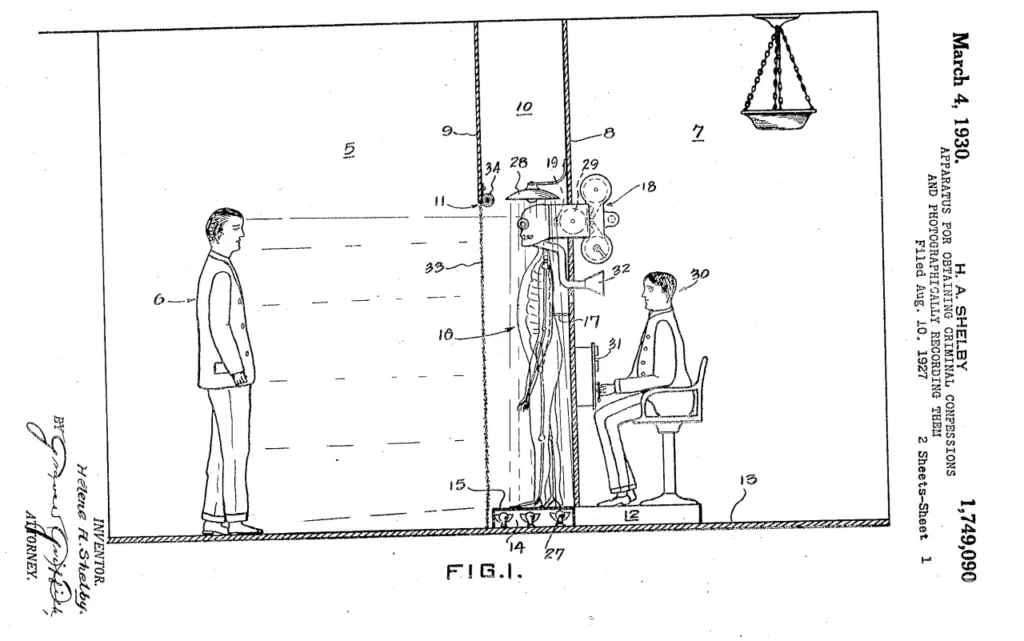

That’s because no police department ever saw fit to put Helene Adelaide Shelby’s 1930 patent for a highly unusual “apparatus for obtaining criminal confessions and photographically recording them” into practice.

Ms. Shelby’s vision sought to transform the police interrogation room into a haunted house where the sudden appearance of the aforementioned skeleton would shock a guilty suspect into confession.

(Presumably an innocent person would have nothing to fear, other than sitting in a pitch black chamber where a truth-seeking skeleton was soon to manifest before their very eyes.)

The idea may have seemed slightly less far-fetched immediately following a decade when belief in Spiritualism flourished.

False mediums used sophisticated stagecraft to convince members of a gullible public that they were in the presence of the supernatural.

Perhaps Ms. Shelby took inspiration from Mysteries of the Seance and Tricks and Traps of Bogus Mediums: A Plea for Honest Mediums and Clean Work by “lifelong spiritualist” Edward D. Lunt. The section on “form materialization” provides plenty of concrete ideas for enacting such trickery.

Ms. Shelby’s proposed apparatus consisted of a “structure divided into two chambers:”

…one chamber of which is darkened to provide quarters in which the suspect is confined while being subjected to examination, the other chamber being provided for the examiner, the two chambers being separated from each other by a partition which is provided with a panel upon one side of which is mounted a figure in the form of a skeleton, the said skeleton having the rear J portion of the skull removed and the recording apparatus inserted therein.

The examiner was also tasked with voicing the skeleton, using appropriately spooky tones and a well-positioned megaphone.

As silly as Ms. Shelby’s invention seems nearly a hundred years after the patent was filed, it’s impressive for its robust embrace of technology, particularly as it pertains to capturing the presumably spooked suspect’s reaction:

The rear portion of the skull of the skeleton is removed and a camera casing is mounted in the panel extending into the skull, said camera being preferable of the continuously-moving film-type an having provisions for simultaneously recording pictures and sound waves, or reproducing these, as may be desired or required, the said camera impression upon the having an objective adapted to register with the nose, or other opening, in the skull. The eye-sockets are provided with bulbs adapted to impress different light intensities on the margins of the film, the central section of the film being arranged to receive the pictures, the variations in the light intensities of the bulbs being governed by means of the microphones, and selenium cells (not shown), which are included in the light circuit and tend to cause the fluctuations of the current to vary the intensity of the light for sound recording purposes, the density of the light film varying with the intensity of the light thus transmitted.

Ms. Shelby believed that a suspect whose confession had been recorded by the skeleton would have difficulty making a retraction stick, especially if photographs taken during the big reveal caught them with a guilty-looking countenance.

Writing on officer.com, Jonathan Kozlowski applauds Ms. Shelby’s impulse to innovate, even as he questions if “scaring a confession out of a guy by being really really creepy (should) be considered coercion:”

Shelby doesn’t seem to have gotten any credit for it and nor am I sure that Shelby was even the first to think of the idea, BUT if you remove the skeleton figure and the red lightbulbs staring into the criminal’s soul was this the inspiration of a mounted surveillance camera?

Allow me to push it even further … imagine your department’s interview room. If you’ve got the camera in the corner (or multiple) let that be. Instead of the skeleton figure just put an officer standing in the corner with a recording body camera. The officer is just standing there. Staring. Sure that’s a MASSIVE waste of time and money – of course. I may be wrong, but if I’m being honest this seems like intimidation.

It also strikes us that the element of surprise would be a challenge to keep under wraps. All it would take is one freaked-out crook (innocent or guilty) blabbing to an underworld connection, “You wouldn’t believe the crazy thing that happened when they hauled me down to the station the other night…”

What sort of horrific special effect could force a guilty party to confess in the 21st century? Something way more dreadful than a skeleton with glowing red eyes, comedian Tom Scott‘s experiment below suggests.

Having enlisted creative technologist Charles Yarnold to build Ms. Shelby’s apparatus, he invited fellow YouTubers Chloe Dungate, Tom Ridgewell, and Daniel J Layton to step inside one at a time, hoping to identify which of them had nicked the cookie with which he had baited his crime-catching hook.

The participants’ reactions at the critical moment ranged from delighted giggles to a satisfying yelp, but the results were utterly inconclusive. Nobody ‘fessed up to stealing the cookies.

That’s not to say the apparatus couldn’t work with a subset of criminals on the lower end of elementary school age. Did they or didn’t they? Why not scar ‘em for life and find out?

Related Content

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.