Humanity has few fascinations as enduring as that with apocalypse. We’ve been telling ourselves stories of civilization’s destruction as long as we’ve had civilization to destroy. But those stories haven’t all been the same: each era envisions the end of the world in a way that reflects its own immediate preoccupations. In the mid nineteen-eighties, nothing inspired preoccupations quite so immediate as the prospect of sudden nuclear holocaust. The mounting public anxiety brought large audiences to such major aftermath-dramatizing “television events” as The Day After in the United States and the even more harrowing Threads in the United Kingdom.

“As a youngster growing up in the nineteen-eighties in a tiny village in the heart of the Cotswolds, I can attest to the fact that no part of the country, however remote and bucolic, was impervious to the threat of the Cold War escalating into a full-blown nuclear conflict,” writes Neil Mitchell at the British Film Institute.

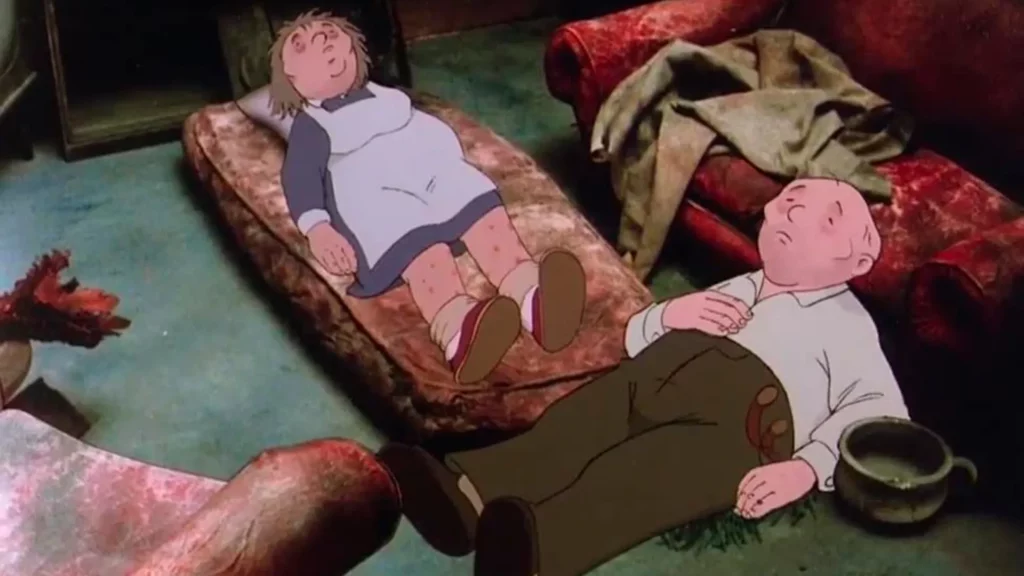

“Popular culture was awash with nuclear war-themed films, comic strips, songs and novels.” This torrent included the artist-writer Raymond Briggs’ When the Wind Blows, a graphic novel about an elderly rural couple who survive a catastrophic strike on England. Jim and Hilda’s optimism and willingness to follow government instructions prove to be no match for nuclear winter, and however inexorable their fate, they manage not to see it right up until the end comes.

In 1986, When the Wind Blows was adapted into a feature film, directed by American animator Jimmy Murakami. Among its distinctive aesthetic choices is the combination of traditional cel animation for the characters with photographed miniatures for the backgrounds, as well as the commissioning of soundtrack music from the likes of Roger Waters, David Bowie, and Genesis — proper English rockers for a proper English production. If the adaptation of When the Wind Blows is less widely known today than other nuclear-apocalypse movies, that may owe to its sheer cultural specificity. It would be difficult to pick the movie’s most English scene, but a particularly strong contender is the one in which Hilda reminisces about how “it was nice in the war, really: the shelters, the blackout, the cups of tea.”

“The couple are fruitlessly nostalgic for the Blitz spirit of the Second World War, convinced the government-issued Protect and Survive pamphlets are worth the paper they’re printed on, and blindly under the assumption that there can be a winner in a nuclear war,” writes Mitchell. “These sweet, unassuming retirees represent an ailing, rose-tinted worldview and way of life that’s woefully unprepared for the magnitude of devastation wrought by the bomb.” You can see further analysis of the film’s art and worldview in the video at the top of the post from animation-focused Youtube channel Steve Reviews. In the event, humanity survived the long showdown of the Cold War, losing none of our penchant for apocalyptic fantasy as a result. However compulsively we imagine the end of the world today, will any of our visions prove as memorable as When the Wind Blows?

Related content:

Protect and Survive: 1970s British Instructional Films on How to Live Through a Nuclear Attack

The Night Ed Sullivan Scared a Nation with the Apocalyptic Animated Short, A Short Vision (1956)

Duck and Cover: The 1950s Film That Taught Millions of Schoolchildren How to Survive a Nuclear Bomb

How a Clean, Tidy Home Can Help You Survive the Atomic Bomb: A Cold War Film from 1954

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.